If you see a notice on your windshield that says, “Parking Fine,” it’s not a compliment.

Are you a University of Oregon student who has skipped paying a Eugene parking ticket? If so, you’re not alone.

It’s like the wild west out there, with thousands of students, locals and out-of-towners ignoring their parking tickets in Eugene.

In 2018, the city declared 8,356 parking tickets delinquent and sent them out for collection. Over the past four years the total sent out for collection reached a staggering 91,621 tickets. And still, a lot don’t get paid.

The city says it doesn’t track unpaid parking tickets by geographic area, so it doesn’t have data on where all the unpaid tickets were handed out, whether the University of Oregon district, for example, has a high delinquency rate.

Frustrated with all the scofflaws and sensitive to the loss of the ticket revenue, for the past four years the city has been sending delinquent parking tickets to Austin, TX-based Linebarger Goggan Blair & Sampson, LLP. Linebarger, a collection agency masquerading as a law firm, is one of the nation’s largest government debt collectors.

“We help communities thrive,” the firm says.

With 46 offices and 112 attorneys across the country, the firm is a money-raising behemoth in the parking ticket business. It claims to collect $1 billion annually in delinquent taxes, traffic citations, parking tickets and tolls.

Some other Oregon cities have contracts with different collection agencies. Bend and Salem for example, have contracts with Professional Credit Service (PCS), a Springfield, OR-based company.

For Bend tickets, PCS adds collection fees of 23% of the total balance and keeps that amount when collecting on a delinquent parking ticket.

In Salem’s case, PCS collects 25% of the principle amount, while the City receives the principle. In cases where there is interest, the City and PCS split this amount evenly.

If a delinquent $10 Salem parking ticket is sent to PCS, the total due becomes $12.50. If 10 cents in interest is assessed before the bill is paid, the total due becomes $12.60. PCVS would retain $2.60 of that and the city $10.10.

Under Eugene’s arrangement with Linebarger, the firm can retain a 20 percent commission of the total amount collected for its work.

Example:

- Parking citation: $100.

- Accrued interest: $21.60 (Interest is calculated at a rate of 18% from the date the account is referred to Linebarger for collection until paid in full)

- Total owed: $121.60 (Parking fine + Accrued Interest).

- Commission to Linebarger: $24.32 (20% of $121.60)

- Payment to City of Eugene: $97.28

If the city’s Parking Enforcement Department places an immobilization device on a vehicle for unpaid fines that have been sent to Linebarger for collection, those delinquent accounts are recalled back to Eugene’s Municipal Court. In such cases, the city isn’t obligated to pay Linebarger a commission for the collection of the citations.

The city considers it reasonable for Linebarger to pursue a collection claim for up to two years. That’s one reason why Linebarger has a reputation for being persistent in its mail and call center collection efforts.

Over the past four years, Eugene has sent delinquent parking tickets with initial fines of $3,072,918 to Linebarger for collection, according to data provided by Jill Wright, a Court Operations Specialist with the City of Eugene, in response to public records requests.

Joe Householder, a Managing Director and spokesman for Linebarger, said the firm’s collection efforts have allowed it to remit $911,003.00 to the city. That represented $627,420.02 in fines and $283,583.98 of interest charges, the city said. This means Linebarger recovered just 20 percent of the original delinquent fines, plus interest.

In other words, a whole lot of delinquent tickets still don’t get paid, even after persistent and extensive efforts to locate delinquent miscreants, forceful letters, and aggressive call centers.

“Our overall results are what matter and our overall results are routinely strong,” Householder said.

“Some accounts take a day to resolve; some take years,” he added. “In some cases, we’ll connect with the person on our first outreach attempt but they’re not ready to resolve the matter – maybe they’re waiting till they get their tax refund, or some other expected money comes in. In those cases, we have to stay in touch week after week or month after month and remind them of the debt.”

“In other cases,” Householder said, “just finding the person can take a long time. They’ve moved multiple times, they’ve remarried and changed their name – any number of factors can make it a challenge.”

So, don’t assume you’re safe because you’ve managed to escape Linebarger’s reach so far. “We continue to pursue collections of the remaining outstanding tickets,” Householder said.

Furthermore, if Linebarger fails to collect the balance on your delinquent parking ticket, and your vehicle is found on a city lot or street, the city may still immobilize the vehicle with a boot device.

Linebarger collects a wide array of receivable types for government clients, primarily payments due on taxes, traffic citations, parking tickets, and tolls.

Much of Linebarger’s work is pretty simple. In Eugene’s case, the Court forwards a record of delinquent parking tickets and Linebarger follows up with letters and pestering recorded phone calls to miscreants urging them to pay up.

“Partnering with Linebarger allows our clients to focus their resources on their core responsibilities, while we focus on locating and contacting the relative few who have continued to ignore their delinquent parking tickets,” the firm’s website says.

To counter the thuggish image of collections agents, Linebarger portrays itself as a company with “a big heart beneath that law firm veneer,” and says its work collecting unpaid bills is helping communities thrive by raising money for parks, schools and essential service.

But it hasn’t been able to avoid some criticism.

For some unexplainable reason, the Better Business Bureau (BBB) gives the Linebarger firm an A+ rating, while at the same time giving it the lowest possible rating, just one star of a possible five, based on customer reviews. Hundreds of complaints have been filed with the BBB against Linebarger nationwide. Complaints range from inaccurate notices of delinquent accounts and rude call center employees to harassing collection calls and allegations of fraudulent charges.

“I am being charged for parking violations in Denver, CO,” wrote one BBB reviewer. “I live in Oregon and have never been to Colorado.”

“I got a letter, that I find threatening, regarding an unpaid parking ticket from 12 years ago,” wrote another reviewer. “Give me a break!”

Yelp reviews are similar, with an overall rating of one star out of 5.

What do Eugene’s Parking Services Manager, Jeff Petry, and City Manager, Jon Ruiz, have to say about all this? Nothing.

Despite repeated requests that they answer a series of questions relating to the parking ticket and collections program, neither responded. So much for government transparency.

______________

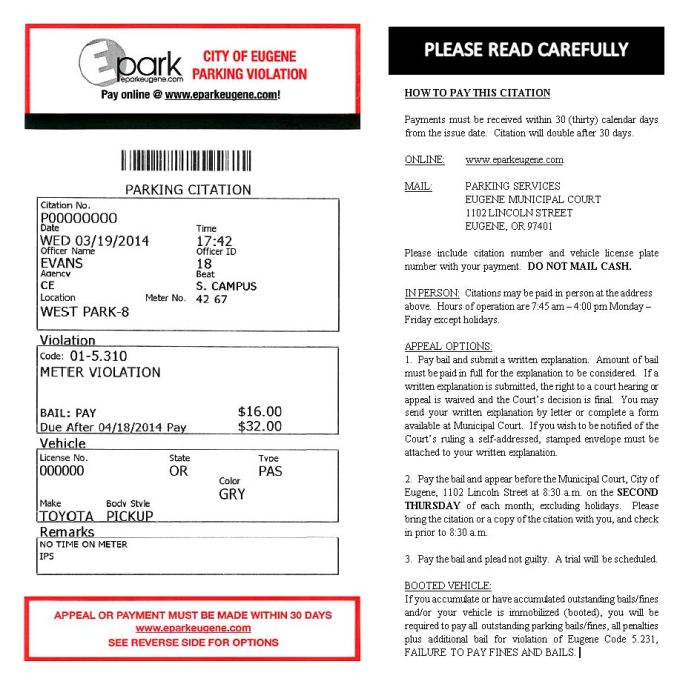

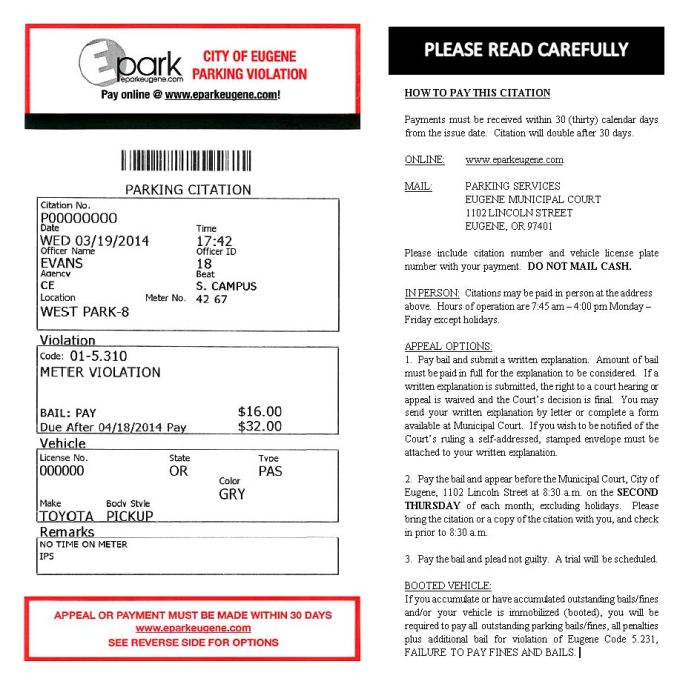

Parking Ticket Fines in Eugene

Overtime Violations

Parking meters and time limits are placed in high use parking areas of Eugene to encourage turnover which increases accessibility for everyone and supports local businesses that rely on street parking for customer access.

Time limit citations in Eugene are $16.

Other Violations

| Violation |

Fine Amount |

Parking in Space Reserved for Persons with Disabilities

First Offense

Second Offense |

$200

$400 |

Storage of Vehicles on Street /Abandoned Vehicle

First Offense

Second Offense |

$25

$50 |

| Parking on Sidewalk, Crosswalk, or in Front of a Driveway |

$25 |

| Parking in a Yellow, Bus, Taxi or Tow-Away Zone |

$25 |

| Parking on wrong side of the street (facing the wrong way) |

$25 |

| Parking in Bike Lane |

$40 |

For more information on parking fines, see the Municipal Court’s Presumptive Fine Schedule.

Fines Increase If Not Paid Within 30 days

Parking citations (tickets) that are not paid or contested within 30 calendar days will double. Citations not paid within 120 days will be sent to a collection agency, and interest will begin to accrue.

Source: City of Eugene, https://bit.ly/2tKY7wC