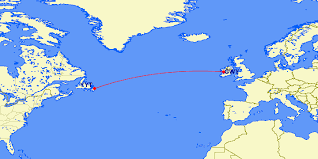

The plane was flying 3500 ft. above the vast Atlantic Ocean.

“Then, just as he was looking at the needle of the air-speed indicator, it froze in front of his eyes. He could smell smoke. Its sensor, mounted above his head, had become packed with sleet and jammed. The indicator was now useless. The turbulent wind made the aircraft sway and judder…To try to get his equilibrium back, he drew back the control column, hoping to pull the nose up. The aeroplane hung motionless for a second. Then it fell into a steep spiral dive.”

Charles A. Lindbergh in a single-engine plane, the Spirit of St. Louis, in May 1927, trying to complete the first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight?

Negative.

It was eight years earlier in May 1919. The courageous pilot was Jack Alcock, a British aviator flying a modified Vickers Vimy bomber powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle engines. Alcock was trying to complete a nonstop flight from St. John’s, Newfoundland, to Clifden, Ireland. Accompanying him as navigator was Arthur Whitten Brown. Brown, nicknamed “Teddy,” was born in Glasgow, Scotland, though his parents were Americans.

I’ve admired Lindbergh since I was a child, thrilled at his derring-do, self-reliance and a triumph of will against the odds. (Yes, I know he also had some less than admirable qualities) On a trip to Hawaii as an adult, I even made a special trip to visit his grave at the end of the road to Hana under the shade of a Java plum tree at Palapala Ho‘omau Church on Maui. I’ve read multiple books about Lindbergh, who became a sensational and lasting celebrity, and I always thought, as most Americans likely do, that he was the first to complete a nonstop transatlantic flight.

Then I came across a fascinating, dramatic, fast-paced book published in 2024, The Big Hop, by David Rooney.

At a time when there seems to be few real heroes, Rooney’s compelling account reveals that Alcock and Brown, both veterans of WW I, were among a hardy group of men who took on the challenge of a contest sponsored by Lord Northcliffe, owner of The Daily Mail newspaper. Northcliffe offered a £10,000 prize to the first aviators to fly non-stop across the Atlantic.

Alcock and Brown were no strangers to peril. Alcock had fought in multiple terrifying dogfights during WWI, earning a Distinguished Service Cross. Brown, captured by the Germans in 1915 after crashing his Flying Corps B.E.2c biplane in northeastern France during WWI, endured atrocious conditions in German prisoner-of-war camps. The camps, often run by sadistic commanders, offered scandalously meagre food rations, were often freezing, swarming with rats and mice, and were inattentive to the multiple injuries and health issues suffered by POWs.

To be eligible for Northcliffe’s prize, competitors had to comply with three basic conditions: the flight had to be between any point in Great Britain and any point in Canada, Newfoundland or the United States; the flight had to be non-stop; the flight had to be completed within 72 hours.

Three teams joined Alcock and Brown in Newfoundland to make the attempt at a continuous Atlantic crossing:

- Harry Hawker and Kenneth Mackenzie-Grieve in a single engine Sopwith Atlantic

- Frederick Raynham and C. W. F. Morgan in a single-engined Martinsyde Raymor

- A team led by Mark Kerr in a four-engined Handley Page V/1500 bomber Atlantic

Hawker had a successful takeoff and managed to fly about 1000 miles, but the Sopwith’s engine failed and the plane went down in the ocean about 750 miles from Ireland. Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve were rescued by a Danish steamer, the SS Mary.

Raynham and Morgan’s plane crashed on takeoff on Newfoundland, likely due to a heavy fuel load and rough terrain.

Mark Kerr’s team abandoned their attempt at a transatlantic crossing after Alcock and Brown successfully crossed the Atlantic.

Alcock later said that when his modified Vickers Vimy bomber fell into a steep spiral dive during the transatlantic flight, the plane “began to perform circus tricks”—plunging toward the ocean while he fought desperately to remain aloft. One moment the altimeter read 1,000 feet, the next only 100. When they were just 65 feet above the waves, he succeeded in regaining control.

On 15 June 1919 a telegram from Alcock and Brown arrived at the Royal Aero Club with the message: ‘Landed Clifden, Ireland, at 8.40 am Greenwich mean time, June 15, Vickers Vimy Atlantic machine leaving Newfoundland coast 4.28 pm GMT, June 14, Total time 16 hours 12 minutes. Instructions awaited.’

As David Rooney wrote in The Big Hop, “Today, a transatlantic flight is an unremarkable part of everyday life. It is almost a chore. But somebody had to go first.”

Memorials at Clifden and London’s Heathrow International Airport also commemorate their achievement.

A statue of Alcock & Brown. Originally on display at Heathrow Airport, it was relocated at the Heathrow Academy but was moved to Clifden in Ireland on 7 May for an eight-week stay to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the flight on 15 June.