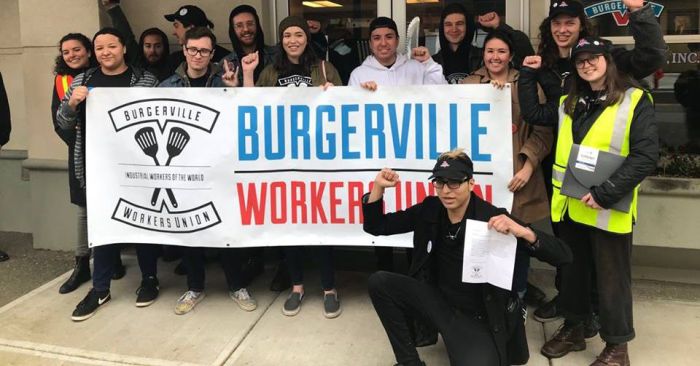

Local news is replete with stories about the failure of contract negotiations between Burgerville and the Burgerville Workers Union ands the threat of a worker strike, but most are failing to point out a critical fact — only 111 Burgerville employees at a total of five of the company’s 47 locations have even voted to form a union.

Furthermore, of the 142 employees who were working in those five locations during their respective votes, only 94 of them were still employed at Burgerville as of mid-2019 and the lead organizers of the unionizing effort at three of the five restaurants no longer worked at the company

It’s also likely that most of the employees now threatening an “imminent” strike will not be at Burgerville long-term because the fast-food industry is grappling with record employee turnover.

According to MIT Technology Review, the turnover rate in the fast-food industry is 150%. In other words, the typical fast food restaurant is seeing its entire workforce, plus half of its new hires, replaced in 12 months.

Burgerville is doing better, perhaps because of its expansive benefits, including health insurance, vacation pay and financial wellness training. Still, the annual turnover rate across all its restaurants in 2018 was 83% (up from 71% in 2017), according to the company.

The union has reportedly asked for a $5 hourly increase for all unionized workers; Burgerville has offered a $1 an hour increase for all workers, which would put them 6 months ahead of a state-mandated minimum-wage increase.

The union says Burgerville’s proposed pay raise is “miserly.” Is it?

According to Glassdoor, a website where current and former employees anonymously review companies and anonymously submit and view salaries, average base pay for hourly crew members is currently $12. When factoring in bonuses and additional compensation, a crew member at Burgerville can expect to make an average annual salary of $25,298.

For comparison, the typical McDonald’s crew member makes $9 per hour, according to Glassdoor. When factoring in bonuses and additional compensation, a crew member at McDonald’s can expect to make an average annual salary of $19,242.

The typical Wendy’s Crew Member makes $9 per hour., Glassdoor says. When factoring in bonuses and additional compensation, a Crew Member at Wendy’s can expect to make an average annual salary of $18,738.

In other words, the average hourly pay of Burgerville crew members is already higher than at key competitors.

Could Burgerville afford to pay its employees more? It’s a private company owned by The Holland Inc., so it doesn’t make its financials public. The economy is strong, however, and the fast-food, or quick service restaurant (QSR), industry in the United States, has been doing well, particularly in 2018 and 2019. Workers have reason to believe Burgerville has benefited.

I understand workers’ desire to share in America’s prosperity, but any increase in wages crunches the bottom line and in a highly competitive marketplace only some of additional labor costs can be passed on to price sensitive consumers. The preferred solution for many fast-food businesses is reducing, not increasing, labor costs, largely by leveraging technology to employ fewer people.

Then, of course, there’s the question of whether the union’s demand for “a living wage” at Burgerville is even realistic.

According to a Living Wage Calculator developed by MIT, A living wage is the hourly rate that an individual in a household must earn to support his or herself and their family. The assumption is that the sole provider is working full-time (2080 hours per year).

The Calculator says a living wage for two adults, with one working, and one child in Multnomah County is $26.06 an hour or $54,205 a year. It is delusional to think Burgerville will pay that much to an easily replaceable crew member with limited skills and an expected short tenure.

The fact is, rather than pushing for unattainable wages at Burgerville, current crew members would be better off enhancing their job skills and/or education to qualify for higher paying employment elsewhere.