There’s a lot of tortured handwringing going on among the mainstream media about how they covered the 2016 presidential race and what they need to do to fix things for 2020.

“…we have a chance to do things differently than we did the last time around – to redeem ourselves,” columnist Frank Bruni opined in The New York Times on Jan. 13, 2018. “Our success or failure will affect our stature at a time of rickety public trust in us.”

Bruni’s column focused on the role of the “mainstream, establishment media” and its responsibility to clean up its act, to avoid writing about the spectacle and cover, instead, substance, fitness for office and competing visions of government.

Sounds all very serious and high-minded. But Bruni’s angst is too late.

The fact is, what the mainstream, establishment print and television media have to say about politics simply doesn’t matter as much anymore because people are going elsewhere to find out what’s going on and what people think about it.

“The conversation that should concern everyone, in both media and politics, is not about what gets covered,” Peter Hamby recently wrote in Vanity Fair. “It’s about what gets attention.”

“At a time when technology is transforming voter behavior at unprecedented speed, this is a problem that the mainstream media, even on its best behavior, cannot possibly solve without a drastic reimagining of what journalism is and how it reaches contemporary audiences.”

Diminishing influence

In 1950, almost every American household read a daily newspaper

In 1950, almost every American household read a daily newspaper. By 2000, only 50 percent of Americans read a printed newspaper on a daily basis.

As I write this in Jan. 2019, I’m sitting at a large, bustling coffee shop. A couple dozen people of all ages are busily engaged at their laptops. Not a single person is reading a newspaper.

The fact is fewer Americans read a daily newspaper today than in 1950, while the U.S. population has more than doubled. And the prognosis isn’t good. With just 2 percent of teenagers reading a newspaper on a regular basis, few are developing a newspaper reading habit.

Unlike the individualized, algorithm-determined, constantly updated news delivered to consumers online, print newspapers offer identical mass communications to their customers. And by the time the news in print newspapers reaches the intended audience, not only is it stale, but it has been superceded by newer news.

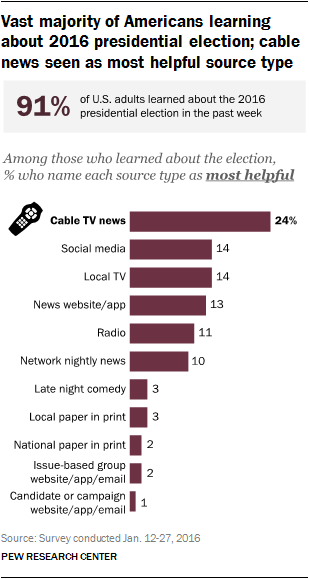

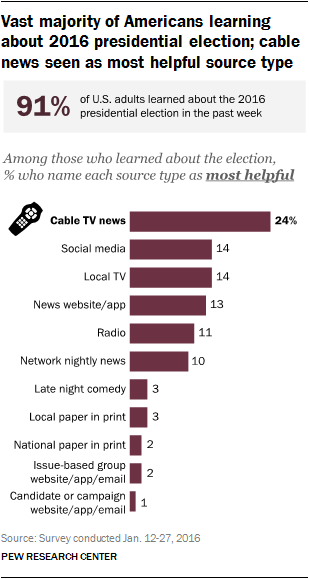

During the 2016 election, a survey of U.S. adults by the Pew Research Center revealed that print versions of both local and national newspapers were named as key sources for election news and information by only 3% and 2% of respondents respectively. Late night comedy shows did just as well as sources at 3%. (Maybe that explains why Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) announced she was forming a presidential exploratory committee during a Jan. 15 appearance on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert”)

And even if you did read print newspapers during the election, policy issues — what the nominees would do if elected—got little press coverage in print outlets. In the 2016 general election, policy issues accounted for just 10 percent of the news coverage—less than a fourth the space given to the horserace between the candidates, according to a Shorenstein Center study.

And even if you did read print newspapers during the election, policy issues — what the nominees would do if elected—got little press coverage in print outlets. In the 2016 general election, policy issues accounted for just 10 percent of the news coverage—less than a fourth the space given to the horserace between the candidates, according to a Shorenstein Center study.

All this has translated into a drastic reduction in the influence of newspaper editorial endorsements.

“Once upon a time, a newspaper endorsement for a political candidate was about as good as it got,” Philip Bump wrote in the Washington Post a couple weeks before the 2016 election. “In the era before the internet…big, important newspapers could shift the fortunes of people seeking the presidency. Nowadays, that’s … less of the case.”

Of the 269 U.S. newspapers that dispensed their wisdom by endorsing a presidential candidate in 2016, 240 endorsed Hillary Clinton and just 18 endorsed Donald Trump. Libertarian Gary Johnson secured nine endorsements and independent conservative Evan McMullin got one.

Of the top 100 largest newspapers in America with the largest circulations, just two endorsed Trump,

As Politico media reporter Hadas Gold tweeted when Trump’s stunning victory became clear, “… newspaper endorsements DO NOT MATTER.”

That may be partly due to slipping public respect for the mainstream media. In a Pew Research Center survey taken shortly after the November 2016 balloting, only one in five respondents gave the press a grade of “B” or higher for its performance. Four of five graded its performance as a “C” or lower, with half of them giving it an “F.”

Declining newspaper circulation

Much of the waning influence of print newspapers can also be attributed to circulation declines (or the reverse).

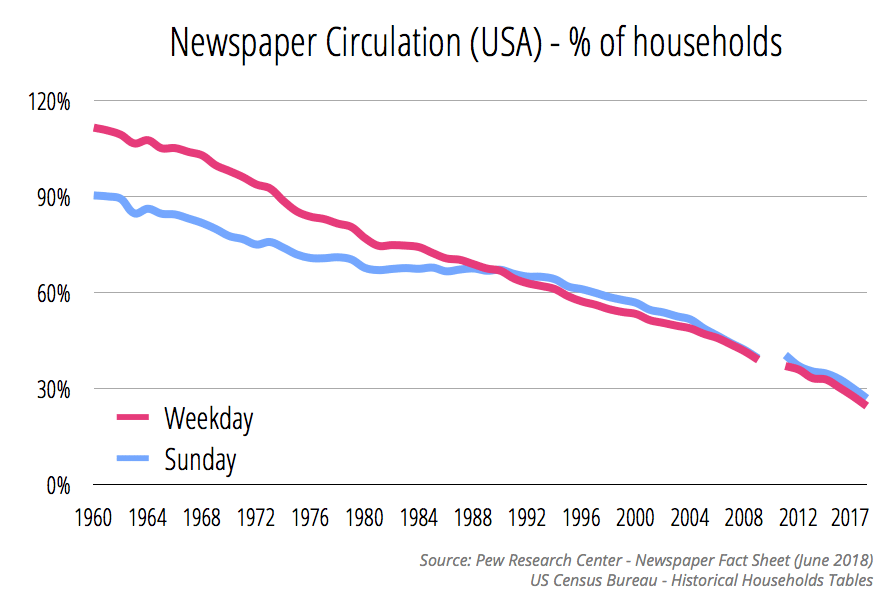

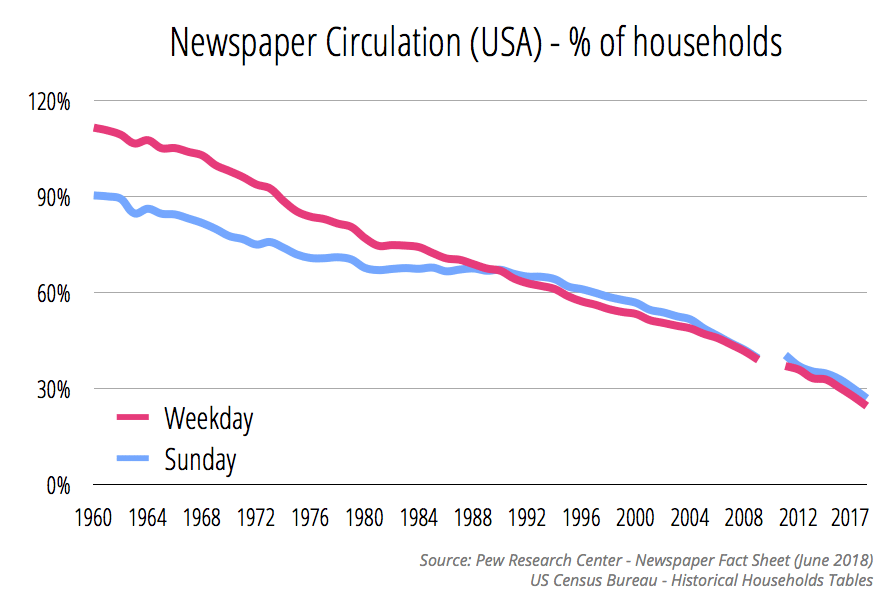

In 1960, nearly 120 percent of households bought a daily newspaper (i.e. there were 1.2 papers sold per household). By 2017, fewer than 30 percent of households bought a daily newspaper.

In 1990, circulation of U.S. daily newspapers totaled 62.3 million weekday and 62.6 million Sunday. By 2009, circulation had sunk to 55.8 million daily and 59.4 million Sunday.

According to the Pew Research Center, in 2016, despite the excitement and turmoil of the national elections, weekday and Sunday circulation for U.S. daily newspapers – both print and digital – fell 8%, marking the 28th consecutive year of declines. Weekday circulation fell to 35 million and Sunday circulation to 38 million – the lowest levels since 1945.

The following year, the first of Tump’s term, was equally discouraging. Estimated total U.S. daily newspaper circulation (print and digital combined) in 2017 was 31 million for weekday and 34 million for Sunday, down 11% and 10%, respectively, from 2016.

Some of that decline is because the United States has lost almost 1,800 papers since 2004, including more than 60 dailies and 1,700 weeklies, leaving 7,112 in the country, according to The School of Media and Journalism at UNC.

California lost the most dailies of any state. In one case, the 140-year-old, 500-circulation Gridley Herald used to serve Gridley (population 6,000) in the central California county of Butte, 60 miles from Sacramento. On Aug. 29, 2018, the paper’s staff and the community were notified by the paper’s owner, GateHouse Media, that the final issue of the twice-weekly paper would be published the next day.

Daily newspaper circulation in California totaled about 5.7 million 15 years ago. In 2018, that was cut in half to 2.8 million.

If print circulation continues to drop at current rates, as many as one-half of the nation’s surviving dailies will no longer be in print by 2021, predicts Nicco Mele, director of the Shorenstein Center for Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University..

One of the most striking examples of decline is in Silicon Valley. The San Jose Mercury News, rebranded as The Mercury News in 2016, was once an influential publication with about 400 reporters, editors, photographers, and artists.

According to The Columbia Journalism Review, the Mercury News was one of the first daily newspapers in the U.S. with an online presence, the first to put all its content on that site, the first to use the site to break news, and one of the first to migrate its growing online content to the web.

Its commitment to innovation and hard news led to daily circulation of 200,258 in 2009 making it the fifth largest daily newspaper in the United States.

But subsequent years of bad business decisions, declining classified advertising (including job listings), layoffs, McClatchy’s purchase of the paper’s owner, Knight Ridder, in 2006, and the subsequent sale of the Mercury News to the MediaNews Group caused the paper to slip. “…sadly the San Jose Merc is a mere shadow of its former self,” commented one online reviewer.

“Not that long ago, the San Jose paper proclaimed itself “The Newspaper of Silicon Valley,” media business analyst Ken Doctor wrote in Newsonomics. “Silicon Valley has done quite well, becoming the global economic engine and driving great regional affluence. But the economically fecund region has become — in less than a decade — a news desert.”

Here at home, The Oregonian, a paper with a long and storied history, is a story of decline, too.

The Oregonian Building, at the corner at the intersection of S.W. Sixth and Alder, occupied by the paper during 1892-1948.

In 1950, when Advance Publications bought the paper, its daily circulation was 214,916. For quite a while, things looked promising.

I joined The Oregonian as a business and politics reporter in 1987. It was a robust, well-respected paper, with a proud past and a much-anticipated future. Daily circulation was 319,624; Sunday circulation 375,914.

When I left the paper 10 years later in 1997 to take a corporate communications job, daily circulation was 360,000, Sunday circulation 450,000. It looked like the paper was on a roll.

But good times were not ahead. By 2012, daily circulation had sunk to 228,599, only slightly higher than in 1950. In subsequent years, daily circulation continued to slump, despite robust population growth in the Portland Metro Area.

Meanwhile, talented reporters have fled in droves, some pushed out, others motivated by buy-outs. At the same time the once powerful paper’s clout has diminished as it has abandoned rural Oregon and 7-day-a-week print distribution.

By 2018, The Oregonian had a print circulation of just 158,000 and distributed to 15 fewer counties in Oregon and Washington than it did in 2004, when it had a circulation of 338,000, according to a UNC report on The Expanding News Desert.

A few smaller local Oregon papers are thriving, but most are suffering, too. And all of them have a tough time covering state and national politics consistently and with any depth.

Oregon Public Broadcasting OPB recently reported that Western Communications, which owns seven newspapers across the West, including the Bulletin in Bend, the Baker City Herald and the La Grande Observer, “is on the brink of foreclosure.” The company hasn’t paid nearly $1 million owed in local property taxes and interest and is between three and five years behind on taxes in counties across Oregon, OPB reported.

Comprehensive political coverage by the Eugene Register Guard is threatened, too. On March 1, 2018, GateHouse Media, the same company that closed the Gridley Herald, acquired the Register Guard, which had survived more than 90 years of independent, family ownership.

GateHouse publishes 130 daily newspapers. It has a reputation for tightfisted financial management accompanied by staff layoffs. It’s impact on the Register Guard has fit that pattern. In Dec. 2017, before the GateHouse takeover, the editorial and news staff at The Register-Guard totaled 42, according to the paper’s staff directory. Today the directory lists 27, of which just 12 are identified as reporters..

Not only has the Register Guard staff shrunk; so has its daily circulation, dropping from 54,325 in 2011 to 41,280 today.

“What’s happening with the Guard isn’t unique to the Guard,” Tim Gleason,professor and former dean at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication, told the Eugene Weekly. “It’s what’s happening all over the country as these venture capital firms buy newspapers and then largely gut them.”

Of course, newspapers are being gutted whether or not they are investment targets.

In early January 2019, the Dallas Morning News eliminated 43 jobs, according to the Columbia Journalism Review, half of them in the newsroom, with the cuts hitting reporters covering immigration, transportation, the environment, and the courts.

On Friday, February 1, The McClatchy Company, which owns properties such as the Miami Herald and the Kansas City Star, emailed staffers to announce that 450 employees would be offered voluntary buyouts as part of a “functional realignment,” essentially signaling that the jobs have been marked out of the budget. The news was first reported by the Miami New Times.

If print newspaper circulation across the board continues to drop at current rates, as many as one-half of the nation’s surviving dailies will no longer be in print by 2021, predicts Nicco Mele, director of the Shorenstein Center for Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard.

None of this is good news if you want an educated, informed public in a position to make wise judgments about public policy.

“The way to prevent irregular interpositions of the people is to give them full information of their affairs through the channel of the public papers, and to contrive that those papers should penetrate the whole mass of the people,” wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1787.

That is as true today.

How about network television news?

Given the decline of local print media, local network TV news is one of the few remaining sources of locally-focused journalism covering political issues, but local TV news has been experiencing declines as well.

Just from 2016 to 2017, the portion of Americans who often rely on local TV for their news fell 9 percentage points, from 46% to 37%, according to the Pew Research Center. Still, local tv news shows have multiple opportunities to cover educate their audience. The problem is that covering public policy is rarely their forte and it’s not what their audience is seeking.

Instead, local TV news is the outlet of choice by adults for weather, breaking news and traffic reports, although young adults are more likely to turn to the Internet, according to Pew Research.

Public policy and politics coverage is also suffering with a decline in the audiences for the national network news shows of NBC, ABC and CBS, although some scholars believe television news viewing has little effect on issue learning. In other words, watching increasing quantities of television news will not lead to greater knowledge about political issues because of the paucity of real issue information. You may know more about polls and personalities, but not so much about political issues that affect your life.

Remember when the family used to gather in the living room every night for the evening news, either the Huntley-Brinkley Report, CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite or ABC Evening News with Frank Reynolds and Howard K. Smith? That was so long ago.

All three network evening news shows have been losing audience steadily since then. By 1998, the three network evening newscasts reached a combined average of only about 30.4 million viewers in a country with a population of 276 million.

In 2016, even with a turbulent presidential campaign, the average viewership for the ABC, CBS and NBC evening newscasts was 24 million, according to a Pew Research Center analysis.

Compare that to the ratings of a single showing of 2016’s number one primetime TV show, The Big Bang Theory, which averaged 19.9 million viewers, or with Super Bowl 50 on Feb. 7, 2016, which got 112.6 million average viewers, according to Nielsen.

By the 2017-18 television season, ABC’s evening news had an average of 8.6 million viewers, NBC Nightly News 8.15 million and CBS Evening News 6.2 million. That’s a total of 22.95 million.

Lonesome Rhodes, a master manipulator.

In Elia Kazan’s classic movie “A Face in the Crowd,” Lonesome Rhodes, played brilliantly by Andy Griffiths, rises from an itinerant Ozark guitar picker to a local media rabble-rouser to TV superstar and a political power. “I’m not just an entertainer. I’m an influence, a wielder of opinion, a force… a force!”, he exclaimed at one point.

Newspaper publishers and TV news anchors may once have felt the same way, but their days are numbered.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the demand for news is going to collapse. It just means there’s going to be a need for more imagination in formatting and delivering it in ways that grab an audience and rewards them for their attention.

Vanity Fair’s Peter Hamby cited a twice-daily news show produced by NBC that runs on Snapchat. According to Digiday, the brief show, Stay Tuned, was created specifically for the vertical-screen mobile experience. In 2018, Stay Tuned averaged 25 – 35 million unique viewers per month on Snapchat, according to data provided to NBC News by Snap. Only one-third of that audience also watches, reads or listens to NBC News content on other platforms, so two-thirds are a new NBC audience.

To top it off, about 75 percent of the “Stay Tuned” audience is under 25 and 90 percent is under 34, according to Snapchat, a significant accomplishment given that reaching younger audiences has provers to be a challenge for traditional print and network TV.

So the future isn’t all grim. It will just be different.