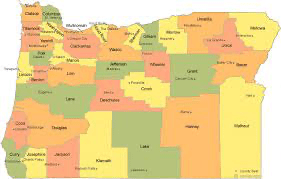

Some folks in Lane County, Oregon want to rename the county because, as the Eugene Register-Guard newspaper put it, Joseph Lane’s “…pro-slavery sentiments and actions against Native Americans don’t align with today’s values.”

Joseph Lane

Joseph Lane, the county’s namesake, was Oregon’s first territorial governor. According to the Register-Guard, he owned at least one slave, a Native American boy, held an “apprenticeship…often recognized as a legalized form of slavery,” over a young man after slavery became illegal, and led actions of violence against Native Americans.

While the re-namers are at it, why not go a whole hog, do a thorough statewide house cleaning? After all, a lot of Oregon’s county names are problematic.

BENTON COUNTY

Thomas Hart Benton, Benton County’s namesake, owned slaves on a 40,000-acre holding where he had a plantation near Nashville, TN. A strong believer in America’s Manifest Destiny, he was also a staunch advocate of the disenfranchisement and displacement of Native Americans in favor of European settlers.

Let’s rename Benton County.

CROOK COUNTY

George R. Crook is Crook County’s namesake. As a member of the U.S. military fought against several Native American tribes in the west, including in Oregon. After the Civil War,he successfully campaigned against the Snake Indians in the 1864-68 Snake War and the Paiute in Eastern Oregon near the eastern edge of Steen’s Mountain.

Let’s rename Crook County.

CURRY COUNTY

George L. Curry, Curry County’s namesake, was the last governor of the Oregon Territory. During the Yakima War against Native Americans, in 1855, Governor Curry raised a force of 2,500 volunteers and led them into battle in support of federal troops.

Oregon prepared for statehood under Governor Curry, approving a state constitution in 1857 that prohibited new in-migration of African Americans and made illegal their ownership of real estate. Although enabling legislation was never passed and the clause was voided by the 14th and 15th Amendments passed after the Civil War, the ban remained a part of Oregon’s constitution until it was repealed in 1927.

Let’s rename Curry County.

DOUGLAS COUNTY

U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Douglas County’s namesake, was the foremost advocate of the view that each territory in the United States should be allowed to determine whether to permit slavery within its borders. He was one of four Northern Democrats in the House of Representatives to vote against the Wilmot Proviso that would have banned slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico.

After marrying Martha Martin in March 1847, her father bequeathed her a 2,500-acre cotton plantation with 100 slaves in Missippi. Douglas hired a manager to operate the plantation while using his allocated 20 percent of the income to advance his political career.

Let’s rename Douglas County.

GILLIAM COUNTY

Colonel Cornelius Gilliam, the namesake of Gilliam County, fought against Native Americans in 1832 during the Black Hawk War in the Midwest and in the Seminole Wars in Florida in 1837. He led volunteer forces in the Cayuse Indian War in 1847 and as colonel of a regiment of volunteers he fought the Walla Walla and Palouse near the Touchet River in the Walla Walla Valley, He was also instrumental in military operations to expel the Mormon colony from Missouri.

Let’s rename Gilliam County.

HARNEY COUNTY

Major General William S. Harney, namesake of Harney County, was commander of the U.S. Army’s Department of Oregon. In 1832, he fought in the Black Hawk War against the Saukj and Fox tribes, which quelled the last Indian resistance to white settlement in the region around Chicago.

During 1835-42, he fought Native Americans in Florida’s Second Seminole War. At the Battle of Ash Hollow in western Nebraska, soldiers under his command indiscriminately killed Brulé Lakota men, women, and children, earning him the sobriquet, The Butcher. According to the Oregon Encyclopedia, Harney was “A brash, opportunistic cavalry officer with an explosive temper and a vindictive predilection for conflict with Indians,” who at one point bludgeoned to death a family female house slave.

Let’s rename Harney County.

JACKSON COUNTY

President Andrew Jackson, namesake of Jackson County, owned a Tennessee plantation, the Hermitage, where he owned slaves. Over his lifetime, he owned a total of 300 slaves and at his death in 1845, he had over 150.

He led troops during the Red Stick War of 1813–1814, leading to The subsequent Treaty of Fort Jackson which required the Creek tribe to surrender vast tracts of present-day Alabama and Georgia. He also commanded U.S. forces in the First Seminole War against Native Americans, which led to the U.S. annexation of Florida. In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act, which forced tens of thousands of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands east of the Mississippi and resulted in thousands of deaths.

Let’s rename Jackson County.

JEFFERSON COUNTY

Jefferson County was named for Mount Jefferson, which was named for President Thomas Jefferson by Lewis and Clark on their westward expedition. Jefferson owned more than 600 slaves during his life. The slaves he owned at the time of his death were sold to pay the debts of his estate.

As US Secretary of State, Jefferson issued in 1795, with President Washington’s authorization, $40,000 in emergency relief and 1,000 weapons to French slave owners in Saint-Dominque (Modern day Haiti) in order to suppress a slave rebellion. When elected president, Jefferson brought slaves from Monticello to work at the White House.

Let’s rename Jefferson County (and Mount Jefferson while we’re at it).

JOSEPHINE COUNTY

Virginia “Josephine” Rollins is the namesake of Josephine County. Her claim to fame was that she was the first white woman to live in the area. That alone might be considered racist enough to justify renaming Josephine County.

Let’s rename Josephine County.

LINN COUNTY

U.S. Senator Lewis F. Linn of Missouri is the namesake for Linn County. He was honored as an early champion of the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850. The Act spurred a huge migration into Oregon Territory by offering qualifying citizens free land just to white male citizens 18 years of age or older who resided on property on or before December 1, 1850. Members of Native tribes were not U.S. citizens and therefore could not own land under the law.

“The DLCA was the only federal land-distribution act in U.S. history that specifically limited land grants by race, essentially creating an affirmative action program for White people,” Kenneth R. Coleman wrote in the Oregon Historical Quarterly. “Perhaps most decisively, the issuance of free land resulted in a massive economic head start for White cultivators and initiated a long-standing pattern in which access to real estate became an instrument of White supremacy and social control.”

Let’s rename Linn County.

POLK COUNTY

President James K. Polk, Polk County’s namesake, was a property owner who used slave labor. He owned a plantation in Mississippi and even increased his slave ownership during his presidency.

Polk inherited 20 slaves from his father and in 1831 became an absentee cotton planter, sending enslaved people to clear plantation land that his father had left him near Somerville, Tennessee. Four years later Polk sold his Somerville plantation and, together with his brother-in-law, bought 920 acres of land, a cotton plantation near Coffeeville, Mississippi and transferred slaves there. He purchased more slaves in subsequent years. In an era when the presidential salary was expected to cover wages for the White House servants, as president Polk replaced them with enslaved people from his home in Tennessee.

Let’s rename Polk County.

SHERMAN COUNTY

William Tecumseh Sherman, Sherman County’s namesake, was a Union hero in the Civil war, but far from an abolitionist. “For one thing, Sherman was a white supremacist,” novelist Thom Bassett wrote in the New York Times in an opinion piece about Sherman’s Southern Sympathies. “All the congresses on earth can’t make the negro anything else than what he is; he must be subject to the white man,” Sherman wrote his wife in 1860. “Two such races cannot live in harmony save as master and slave.”

History had forced the institution of slavery on the South, Sherman thought, and its continued prosperity depended on embracing it, Bassett wrote. “Theoretical notions of humanity and religion cannot shake the commercial fact that their labor is of great value and cannot be dispensed with.”

Let’s rename Sherman County.

WASHINGTON COUNTY

And let’s not forget Washington County.

President George Washington was the namesake for Washington County.

One of the original four counties of the Provisional Government in Oregon and first called Twality, the county was renamed in 1849 in honor of the president.

Washington’s Virginia estate, Mount Vernon, was home to hundreds of enslaved men, women, and children, on who’s labor he depended to build and maintain his household and plantation. Over the course of his life, at least 577 enslaved people lived and worked at Mount Vernon. At his death, Mount Vernon’s enslaved population totaled 317 people. In his will, he ordered that his slaves be freed at his wife’s death, but that request applied to fewer than half of the people in bondage at Mount Vernon. Those owned by his wife’s estate were inherited by Martha Washington’s grandchildren after her death.

According to the Mount Vernon plantation’s current website, “After the Revolution, George Washington repeatedly voiced opposition to slavery in personal correspondence. He privately noted his support for a gradual, legislative end to slavery, but as a public figure, he did not make abolition a cause. “

Time to change the name of Washington County, too, don’t you think?