It’s not right. It’s not wise.

It’s just not fair to the students at Lynch Meadows, Lynch Wood and Lynch View elementary schools in Portland’s Centennial District.

The three schools are set to lose the “Lynch” in their names before the next school year because the District decided the name “Lynch” is an epithet. Many newer families coming into the district associate the name with America’s violent racial history, Centennial Superintendent Paul Coakley told The Oregonian.

This is (supposedly) adult educators gone mad.

What’s next? Renaming public buildings with names such as White ( lacks tolerance of diversity), Young (implies ageism), Jackson (he owned slaves,, you know), Wilson (a president who re-segregated the federal civil service) or Johnson (President Andrew Johnson obstructed political and civil rights for blacks after the Civil War, contributing to failure of Reconstruction.)

The overly censorious policing of language in order to spare sensitive young minds does the children no good. Instead of protecting the delicate young souls, it lays the foundation for later insistence on trigger warnings, objections to micro-aggressions, the shouting down of controversial speakers, and the unfortunate spread of presentism, the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts.

The correct response by the Centennial School District was not to cater to misconceptions about the word by abolishing its use, but to educate the schoolchildren about the historical roots of the use of the Lynch name at the schools and the philanthropic spirit of the Lynch family, and, yes, that the word “lynch” in America is also associated with the killing of black people, often by racist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan.

As Jeremy Montgomery, whose son attends Lynch View Elementary School, told KATU, education would be a better solution. “See, I didn’t even know that (the schools were named after a charitable family). If people were more open to that and knew that, I couldn’t see it being a problem at all,” he said.

Tom Singerhouse, who went to Lynch View more than 50 years ago, expressed a similar view to KATU, saying teachers should be teaching their students about the significance of the Lynch family.

Lynch Wood Elementary’s website already provides a history lesson about the school’s name. Take a look (below). It’s fascinating reading and would be a good basis for a valuable history lesson with the schools’ students. They’d certainly learn a lot more than they would from deleting “Lynch” from their school’s name.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

A History of Lynch Schools

A booklet produced by the Civic Leadership Class of 1964

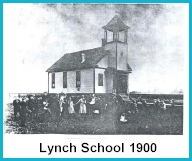

The name “Lynch School” dates back to 1900 when a one room school was built on the present site of the Lynch School at S.E. 162nd Avenue and Division Street, says a website a reprint of a booklet produced by the Civic Leadership Class of 1964.

According to the booklet, on March 13, 1900, Patrick and Catherine Lynch donated one acre of ground located at Section Line Road (Division) and Barker Road (162nd Ave.) on which was built a new one room school pictured on the front of this booklet.

This is the origin of the name “Lynch.” The Lynch farm originally consisted of 160.3 acres granted to Patrick and Catherine Lynch on August 1, 1874, under the Homestead Act passed by Congress in 1862. The original deed granted the land to the Lynch family and was signed by Ulysses S. Grant, President of the United States. Although the property included land on both sides of Section Line Road, the farm home was located across Division Street in the vicinity of The Hut, a restaurant now situated at 167th and Division.

The deed to the property donated to the Lynch School District in 1900 describes the location of the survey markers marking the boundary of the property as being located three inches below the wheel ruts in the adjoining roads. The stone markers had chiseled grooves on the top side for identification purposes. The stone marking the corner of the property at S.E. Division 10″ x 15″ x 22″ set flat side down 3″ below surface of gravel in the north wheel rut of graveled Section Line Road and tamped firmly in place”.

The area around the Lynch School was entirely devoted to agriculture in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Threshing was a community undertaking and many boys missed school because they were needed at harvest time.

The original one room Lynch School which started with fifteen to twenty students increased in number until in 1914 there were about fifty students in the one room school. Some say there were as many as sixty for the one and only teacher. Some of the former students of those “good old days” say that the only way the teacher could handle all eight grades was to divide up her time so each class had a recitation period. She would start in the morning with the first grade, and would by afternoon, finally get around to the eighth grade.

Meanwhile, the rest of the classes were working on assigned work. Of course, some activities and classes were jointly carried on together, such as music, writing practice, and practicing for school plays. In 1915 a large multiple purpose room, which served as an auditorium and meeting place for community functions was built onto the existing one room school. Folding doors were extended during the day making it into two classrooms giving the school a grand total of three rooms.

The Lynch P.T.A. was first organized in 1917 and undertook as its main project, the serving of hot soup and chocolate at lunch time. Residents who remember those days, say it was prepared at the W.B. Steel home where the Big Dollar Shopping Center is now located. Several of the boys would be asked to go over and carry back the kettles of soup and cocoa along with a pail or two of water before lunch.