What’s in the water in Salem?

On one side you have a phalanx of Democrats proposing the ludicrous idea of paying strikers unemployment benefits, which would make Oregon the only State in the country to grant unemployment benefits to striking public and private sector workers.

Not to be outdone in making nonsensical proposals, now you have a raft of Republicans, mimicking President Trump, proposing that the state forego taxing tips.

Here’s a tip – exempting tips from state taxes is a bad idea.

In their determination to position themselves as supporters of the working man (and woman), 21 of Oregon’s House Republicans have proposed a bill, HB 3914, to end taxation of tips, which are generally perceived as discretionary payments determined by a customer that employees receive from customers.

As written, the bill would not count “service charges” as tips. A restaurant, for example, recently added an automatic service charge equal to 18% of my bill. Even if that was intended to cover for a “no tipping” policy, it would be part of the server’s wages because it was not discretionary.

The 129-word Oregon bill gets right to the point, “There shall be subtracted from federal taxable income any amount of tips properly reported as wages on the taxpayer’s federal income tax return.” That would automatically subtract tips from taxable income in Oregon, too.

The bill deserves a quick death.

According to the IRS, “All cash and noncash tips received by an employee are income and are subject to Federal income taxes. All cash tips received by an employee in any calendar month are subject to social security and Medicare taxes and must be reported to the employer.” So, tip income is taxable income.

Charges automatically added to a customer’s check by an employer and subsequently distributed to employees are not tips; they are “service charges”. These service charges, which are appearing more often on Oregon restaurant bills, are non-tip wages and are subject to Social Security tax, Medicare tax, and federal income tax withholding.

Many consumers think the expanding pressure on customers to leave tips is already out of hand. A no tax on tips policy would likely expand the use of tipped work even further, potentially leading to consumers being asked to tip on virtually every purchase everywhere.

A New York Times article about tipping generated a lot of comments, many of which lamented the seeming spread of tipping expectations to multiple businesses and regardless of the amount of actual service by an employee. “Collectively, we cringe when the iPad is swiveled into our face at the coffee counter or deli; we know it is extortion rather than appreciation for services rendered,” said one person.

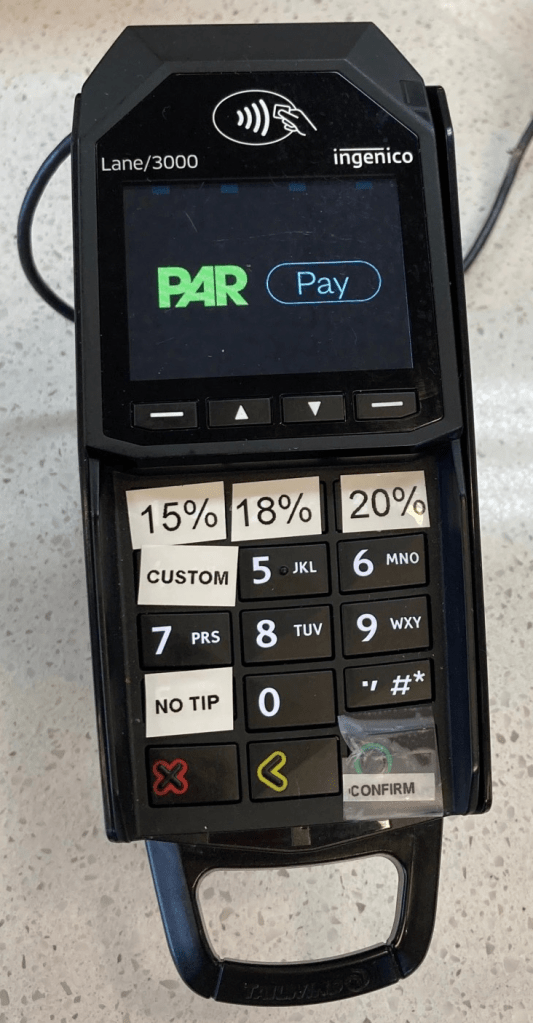

There’s also a sense that some businesses are customizing the tip configuration on screen to exploit customers. Most people tip between 15-20%. If you buy a $2.85 espresso and the screen offers 15%, 20% and 25% tip options, you are likely to hit 15%, generating a tip of 43 cents. If a business wants to jack that up, however, it can give you $1, $2, or $3 options on purchases below $10, instead of a percentage. If you pick $1, you have paid a 35% tip. Devious, but effective.

Despite the massive increase in tipping expectations in recent years at multiple businesses, tax experts say a relatively small share of the workforce depends on tips. Only about 2.5% of American workers are in occupations that depend on tips, according to the IRS. Among those workers, 37% earn less than the federal standard deduction. So, they already don’t have to pay federal income taxes.

Other tipped workers benefit from the earned income tax credit (EITC) and/or child tax credit (CTC) to the extent that they don’t have any federal income tax liability. In addition, because tipped workers would keep more of their income, employers could use this law as a justification for lowering workers’ base pay if it is currently above the minimum wage.

In fact, exempting tips from taxation can actually lead to situations where low-income workers end up effectively losing income through losing eligibility to tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC).

The Budget Lab at Yale, a non-partisan policy research center, estimates that less than 3 percent of families would benefit from a broad-based income tax deduction for tips in 2026, but it would still cost the federal government more than $100 billion over the next decade. Restricting eligibility to workers in the leisure and hospitality industries would reduce the cost by more than 40 percent, but that would still leave a big hit on the deficit unless taxes were raised elsewhere.

Even the liberal Oregon Center for Public Policy opposes the no tax on tips idea.

In October 2024, Daniel Hauser, Deputy Director of the Center, said that ending taxes on tips “makes the tax system less fair” because workers receiving tips would get a tax break, but not low-paid workers in general.

If you have two workers, one a bartender who earns about $10,000 of his $40,000 annual income in tips and the other a warehouseman who makes all of his $40,000 income in wages, it wouldn’t make sense to give the bartender a tax break but leave the warehouse worker hanging out to dry, Hauser argued.

It also “creates openings for people to think about, how can my income be categorized as a tip and get this tax break too?,” Hauser wrote. Third, he said, “if the goal is to help the economic security of low-income workers, it’s not very effective…and there are much better ways for us to try and help low-income families in Oregon.”

He’s right.