In Connecticut and elsewhere in New England, “All the best families owned ‘captives’.” – Anne Farrow, “The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory” (Wesleyan University Press).

A Hartford (CT) Courant notice of 24 May, 1773, concerning the availability for sale of a 28-year old mother and her two sons.

As Oregon, where I now live, has been coming to terms with its racist past*, I’ve found myself wondering whether Connecticut, where I grew up before moving to Oregon in 1984, shared some of that history.

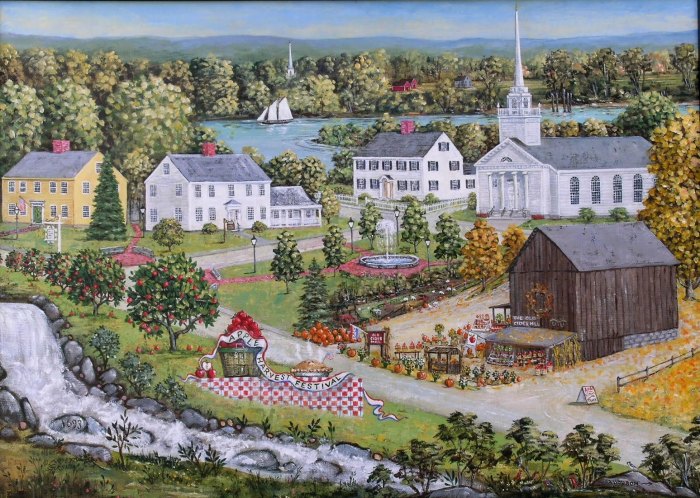

Ahh, colonial Connecticut. Hardy Yankee farmers, white clapboard churches with tall tapering steeples, networks of grey stone walls, one-room schoolhouses….

Ye olde Connecticut village

…and slaves.

Before the Civil War, nearly 4 million black slaves toiled in the American South. That’s the story we all learned in school, that slavery, with all its brutality, abuse and inhumanity, meant the South, just as many of us were mistakenly told that slavery was a uniquely American institution.

That’s what I was told when I grew up in the Connecticut town of Wallingford, settled in 1670, 50 years after the Mayflower’s 102 pilgrims landed at Plymouth.

I’m a descendent of one of the town’s original settlers, Samuel Hall, and of one of its most famous residents, Lyman Hall, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who was born and raised in Wallingford. So you’d think I’d be well versed in Connecticut’s history.

But I wasn’t told during my schooling that in the ancient world, slaves were common. Even in 5000 B.C., Uruk, considered the first city (in what is now called Iraq) had slavery. Most of the slaves then were captured in war, convicted criminals, or people heavily in debt.

As Kay Hymowitz, a Fellow at the Manhattan Institute has pointed out, slavery was a mundane reality in most human civilizations, appearing in the earliest settlements of Sumer, Babylonia, China, and Egypt, and it continues in some parts of the world to this day.

In North America, slavery was also endemic among Indian tribes before Europeans arrived. Andrés Reséndez describes in The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America (2016), the economy of the Comanche empire, based in central Texas, was based on human predation and the slave trade; the Comanches sold captured Indians, Mexicans, New Mexicans, and other Americans to any willing buyer.

I also wasn’t taught about all that, although the underground railroad helped escaping southern slaves in Connecticut, slavery flourished there at the same time.

According to the Medford, MA Historical Society, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island were the three New England states with the largest slave population during the colonial period. Rhode Island had the largest proportion of slaves. It is likely that by the mid 1700’s, there were as many as one African for every four white families in these three states.

Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island were the three New England states with the largest slave population. Rhode Island had the largest proportion of slaves. It is likely that by the mid 1700’s, there were as many as one African for every four white families in these three states.

In other words, colonial Connecticut was hardly a citadel of racially progressive thought and practice. For many Africans, it was a citadel of broken dreams.

It was a place of broken dreams for many Native Americans as well.

History of Slavery in Connecticut, published in 1863, pointed out that the earliest slavery in Connecticut wasn’t of blacks from Africa, but Native Americans captured in battle and sold as slaves. I don’t recall that being highlighted in my classes either.

In fact, the Articles of Confederation of the United New England Colonies, signed by representatives of the Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Haven colonies, even stipulated that the signatories would equally distribute any “ persons,” lands, and goods “ taken as the spoils of war.”

King Philips War, during 1675 to 1676, which pitted Native American leader King Philip, also known as Metacom, and his allies against the English colonial settlers, produced a large number of native slaves.

In 1637, Connecticut colonial leaders, together with their Narragansett native allies, massacred the largest Pequot village at Misistuck on the Mystic River in present-day Connecticut, destroying it and killing an estimated 700 Pequots, including many women and children. Another 180 Pequots were killed when they were found hiding in a swamp near today’s Fairfield, CT. Many of the Pequots were captured and sold as slaves, leading to the near annihilation of the tribe.

The Pequot War

A fascinating study by Linford D. Fisher, associate professor of history at Brown University, finds that Native Americans, including noncombatants, who surrendered during King Philip’s War to avoid enslavement were enslaved at nearly the same rate as captured combatants.

Fisher’s study, “‘Why shall wee have peace to bee made slaves’: Indian Surrenderers during and after King Philip’s War,” appears in the journal Ethnohistory, a volume devoted to scholarship on indigenous slavery in the New World.

Native American slavery “is a piece of the history of slavery that has been glossed over,” Fisher said. “Between 1492 and 1880, between 2 and 5.5 million Native Americans were enslaved in the Americas in addition to 12.5 million African slaves.”

While natives had been forced into slavery and servitude as early as 1636, it was not until King Philip’s War that natives were enslaved in large numbers, Fisher wrote in the study. The 1675 to 1676 war pitted Native American leader King Philip, also known as Metacom, and his allies against the English colonial settlers.

During the war, New England colonies not only retained many defeated native Americans as slaves, they routinely shipped Native Americans as slaves to Barbados, Bermuda, Jamaica, the Azores, Spain and Tangier in North Africa, Fisher said.

“The shadow of native enslavement in New England extends into the 18th century and beyond,” Fisher said. “There are records of people petitioning for freedom in the 1740s who were the descendants of Native Americans first enslaved during King Philip’s War.”

Black slaves were also very much a part of early New England. “Slaves were widely viewed as an economic necessity in colonial New England,” according to the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme Connecticut. The Museum cites a letter to John Winthrop (1588–1649), governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, from his brother-in-law Emmanuel Downing (1594–1676) advised in 1645: “I doe not see how wee can thrive untill we get into a stock of slaves suffitient to doe all our buisines.”

“As the town (Old Lyme) grew and prospered, governors, judges, military officers, ministers, deacons, doctors, merchants, mill owners, tavern keepers, and well-to-do farmers all owned slaves,” according to the Museum. ” Sea captains, shipyard owners, ship’s joiners, deckhands, coopers, blacksmiths, carpenters, mill workers, farmhands, shad fishermen, and day laborers benefited, in turn, from Lyme’s coastal trade.”

Rhode Island was one of New England’s states particularly active in slavery.

“Newport (R.I) was the first landing place for most of those people…who set foot on Jamestown (R.I) in bondage,” wrote historian James Fay of the Jamestown Historical Society. “They arrived here from across the bay in Newport, the center of the American-owned slave trade, the port where 965 Rhode Island ships carried people of Africa to the British West Indies and southern American ports, Barbados, Jamaica, Antigua, the ports of Savanah and Charleston, and occasionally, to Newport. These Rhode Island ships, though only a tiny part of the Atlantic slave trade, carried 106,000 people to the Americas. These people were purchased by Rhode Island captains from African traders who had captured and enslaved them in wars and raids upon each other to enrich themselves at the expense of their enemies, and to feed the insatiable demand by Europeans for slaves.”

Even the Newport Town Council got into the slave business. Fay wrote of how the entire Martin family of Jamestown – the mother Peggy and her five children Newport, Peggy, Jude, Jacob, and Jamestown; the men Mintus and Abraham Martin –were sold to new owners or indentured to free the town of the debts of their owner, Rebecca Carr Martin.

It’s also worth knowing that the slaves who ended up in New England were a very small proportion of Blacks brought across the Atlantic from Africa.

Most of the Blacks taken from Africa were sold to enslavers in South America or the Caribbean. British, Dutch, French, Spanish and Portuguese traders brought their captives to, among other places, modern-day Jamaica, Barbados, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Brazil and Haiti, as well as Argentina, Antigua and the Bahamas, according to an exhaustive SlaveVoyages database considered in depth in a New York Times story, Quantifying the Pain of Slavery.

Only slightly more than 3.5 percent of the total, about 389,000 people, arrived on the shores of British North America and the Gulf Coast during those centuries when slave ships could find port.

Some of those found themselves owned by Theophilus Jones (1690-1781), who came to Wallingford in 1711. He built up his farm property and c. 1740 built a house on Cook Hill in the southwest corner of town, now 40 Jones Rd. His son, Theophilis Jones, Jr. (1723-1815) a documented slave owner, continued to amass land at the site.

The house, which is still standing, is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

Theophilus Jones house, Wallingford, CT

Another slave-owner’s house still standing in Wallingford is the John Barker House, built in 1756.

John Barker house, Wallingford, CT

Slaves were brought into New England throughout the colonial period through multiple port cities:

- Portsmouth, NH

- Salem, MA

- Boston, MA

- New Bedford, MA

- Providence, RI

- Bristol, RI

- Newport, RI

- Middletown, CT

- New London, CT

Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island ended up having the largest slave populations, though they were far from alone among northern states in accepting slavery.

Slavery continued to exist in New York, without any protest against it, until the Quakers took action in the 1760s to free the slaves held by their members, according to a 1925 History of Westchester County, New York by Alvah P. French.

In 1767, Purchase Quarterly Meeting sent the following minute to the Yearly Meeting, then held at Flushing: ” If it is not consistent with Christianity to buy and sell our fellowmen for slaves, during their lives and their posterity after them, then whether it is consistent with a Christian spirit to keep those in slavery that we have already in our possession by purchase, gift or any other ways.” The subject was continually before their meetings until the last slave held by a Friend was set free, in 1779.

Others followed the example set by the Quakers in freeing their slaves, so that, by the end of the century, but few slaves remained in the county. All slaves in the State of New York were made free by law on 4th of July, 1827.

When the Quakers of Purchase liberated their slaves they settled them on their rough lands in the northwestern portion of the town of Harrison, and thus the negro community, still existing northeast of the village of White Plains, was begun. Some of the slaves liberated in the northern portion of the county collected into a smaller settlement near the village of Bedford. These were the largest colonies of negroes in the county.

If you’ve ever visited the historic Faneuil Hall Marketplace in Boston, MA, you may be surprised to learn that Peter Faneuil, who donated the site to the city, accumulated much of his substantial wealth from the slave trade.

Faneuil Hall, Boston

Slaves were also in evidence at tobacco farms in the Connecticut River Valley as early as the seventeenth century. Tobacco was introduced when seeds were brought from Virginia in 1640.

Tobacco production was significant enough that the Connecticut Town of Windsor found it necessary to appoint an “Inspector and Presser of Tobacco,” to supervise the grading and packing of tobacco in hogsheads for shipment to the West Indies, South America, and Europe. According to an overview of the Windsor Farms Historic District, Black slaves and semi-indentured Indians provided most of the labor on the larger farms.

Archaeologists from Central Connecticut State University came across what looked like a 13,000-acre plantation, the second largest in southern New England, in Salem, CT. According to the Hartford Courant newspaper, the owners may have imported 60 slave families to clear the land and relied on slave labor to operate the plantation.

At the start of the Revolutionary War, when the Salem plantation was confiscated because the owner was a Tory, it had just nine slaves (Great Prince, Little Prince, Luke, a woman named Prue and children named Cato, Phillis, Rose, Jimm and Caesar) . The adults were valued at 200-450 pounds each, 6-month-old Jimm and 11-year-old Caesar at 10 pounds.

A smaller plantation of 3,000 acres with at least two dozen slaves also existed in Pomfret, CT, the Courant reported. When the owner transferred ownership of the estate in 1764, the deed included an inventory that included 27 negroes. The document identified the slaves by the names “Prince, Harry, Pero, Dick, Tom, Adam and Christopher, all Negro men, and Dinah, Venus, Rose, Miriam, Jenny and [a second] Rose, all Negro women… ” along with their children “Primus, Christopher, Sias [sic], Sharper and Little Pero.”

Similarly, John Easton’s family in Middletown, CT were leading slave merchants.

In “The Logbooks: Connecticut’s Slave Ships and Human Memory,” Anne Farrow wrote about the ship Africa, with John Easton as its captain, sailing out of New London, CT in 1757 bound for West Africa. It crossed the Atlantic Ocean, sailed up the Sierra Leone River on the west side of the continent, docked at tiny Bunce Island and loaded a cargo of slaves to be sold principally on England’s colonial islands in the Caribbean. Some of the “human cargo” probably stayed on board to be brought to Connecticut, where they were sold and owned by residents there, Farrow said.

According to the Hartford Courant, when John Easton died in 1774 his will contained 20-page inventory of his property, which included two Negro men, Accrow, valued at 100 pounds, and Gambo, valued at 25 pounds.

That same year, The Connecticut Journal reported that John Ive’s slave, Lemon, was “taken to the Gaol in New Haven for abusing an Indian girl” and was sentenced to “sit on the Gallows with a rope about his neck one hour and then whips 39 stripes at a Cart’s Tail.” There was also an incident in which a man named Phineas Cook brought a Portuguese man to Connecticut and sold him as a slave. The matter went before Connecticut’s General Assembly which fined Cook and ordered him to return the man to the Cape Verde archipelago off the west coast of Africa.

By the way, it was in the following year, 1775, that the Rev. Samuel Andrews, a committed Tory, is reported to have preached the first sermon against slavery in Wallingford’s Episcopal Church.

Slaves were also mentioned in the list of items Dr. William Hart of Wallingford left to his wife upon his death in Oct. 1799. The items included “…an inkstand, three iron pots, one spider, a Negro boy named Titan, and a Negro girl of five years.”

Some Wallingford residents began freeing their slaves, however, after the Declaration of Independence, spurred on by a law enacted by Connecticut’s General Assembly in 1777 stating that if “any slaveholder shall apply to the selectmen for liberty to emancipate his slaves, it shall be the duty of the selectmen to enquire as to the ability of such slave to support himself, and if found capable, give the slaveholder a certificate of liberty to free the negro.”

According to town records, 17 slaves were given their freedom by residents from 1778 to 1786 by the following local residents: Ruth Merriam; Rachel Johnson; John Hough; Gould; Norton; Martha Doolittle; Miles Johnson; John Barker; Dr. Jared Potter; Samuel Street; Elisha Brockett; Turhand Kirtland; Edward Barker; Abner Rice; and Thomas Hall.

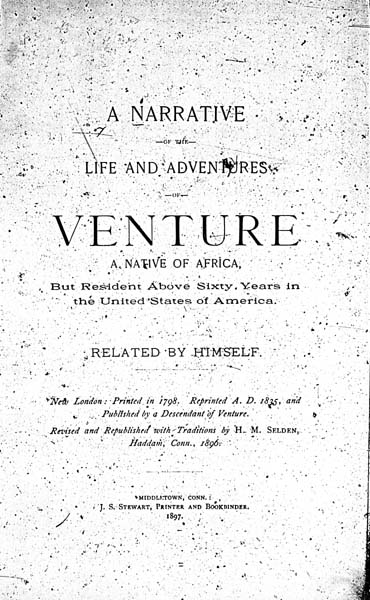

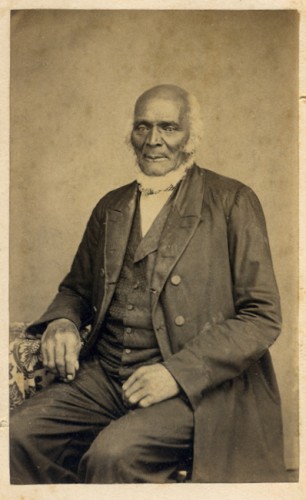

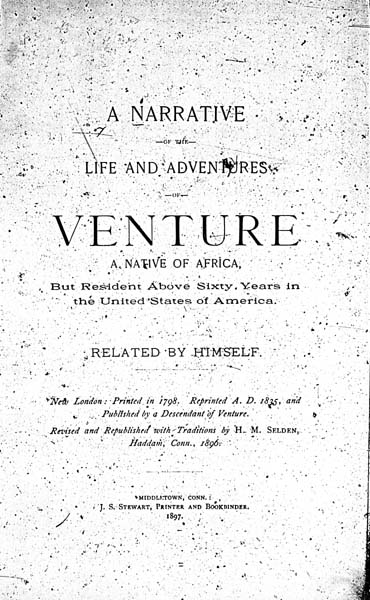

One of the few first-hand written accounts of an African being enslaved and shipped to the New World is Venture Smith’s A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa: But Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America. Related by Himself, published in New London, CT in 1798.

Smith (His African name had been Broteer, 8-year-old son of Saungm Furro, Prince of the Tribe of Dukandarra in Guinea) was taken captive in West Africa around 1730 and taken to the coastal slave-trading center Anomabo (in present-day Ghana) for sale. Broteer later recalled that an officer on a Rhode Island slave ship purchased him for “four gallons of rum and piece of calico cloth.” Most of the captives were later sold in Barbados, but Smith went on to Newport, RI and spent the next three decades as a slave in New York and Connecticut.

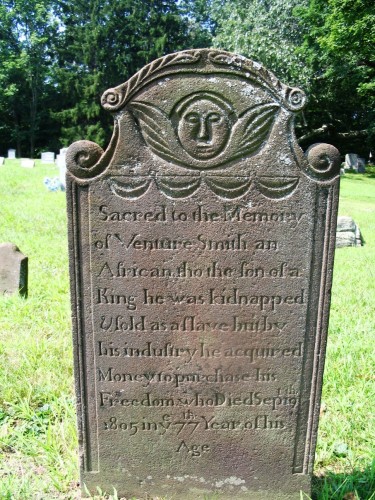

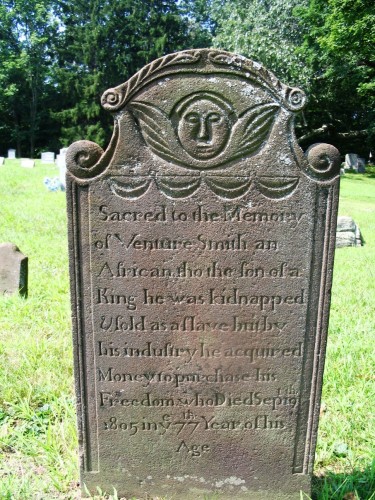

Venture Smith died in 1805. He was buried in the graveyard of the First Congregational Church in East Haddam, CT, along with his wife, Meg, and other members of their family. Smith’s gravestone can be seen there to this day.

“Sacred to the memory of Venture Smith, an African. Tho the son of a King he was kidnapped and sold as a slave but by his industry he acquired Money to Purchase his Freedom.” Venture Smith gravestone.

William Grimes, who arrived just after 1800, was among the first runaway slaves from the South to reach Connecticut and New Haven. Grimes later published “Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave,”an autobiographical account of slavery in the South and the treatment of African Americans in the North during his lifetime.

In Sept. 2018, he was inducted to the Connecticut Freedom Trail location at New Haven’s Grove Street Cemetery , where he is buried, for his pioneering contribution to U.S. history. Grimes’ great-great-great-granddaughter, Regina Mason, was a speaker at the event.

In 1811, George Washington Stanley Esq. , the son of Wallingford resident Oliver Stanley, wrote a brief manuscript history of Wallingford for the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences and sent it to Prof. Silliman of Yale. The report noted that of Wallingford’s 2,325 inhabitants, there were “1,152 white males,1,147 white females, 22 of color and four slaves, also ten foreigners, natives of England and Ireland.”

For nearly two hundred years New England maintained a slave regime that some historians used to claim was quite different from in the South.

Instead of slaves performing mainly agricultural labor, as in the South, the Medford (MA) Historical Society and Museum says New England’s slaves performed more varied jobs. “Owned mostly by ministers, doctors, and the merchant elite, enslaved men and women in the North often performed household duties in addition to skilled jobs,” the Society says. “They worked as carpenters, shipwrights, sailmakers, printers, tailors, shoemakers, coopers, blacksmiths, bakers, weavers, and goldsmiths. Many became so talented in the crafts that the free white workers lost jobs to them.”

But the idea that New England slaves were not situated on large agricultural properties has been refuted by other historians.

A 1764 inventory of “living creatures” on a 3000 acre plantation in Pomfret, CT listed 80 cows, 45 oxen, 30 steers, 59 young cattle, six horses, 600 sheep, 180 goats, 150 hogs and 27 Negroes, in that order.

Slaves working on a New England farm

And in 2015, Central Connecticut State University archeologists uncovered in Salem, CT the remnants of a large plantation that was worked by as many as 60 slave families in the years before the American Revolution.

According to research by the Hartford Courant, the creation of that plantation began in 1718 when Col. Samuel Browne, a wealthy Salem, MA merchant, began amassing land. He rented out some tracts, retaining about 4,000 acres for himself. That passed to his son and then to his grandson.

In 1690 there were only an estimated 200 black slaves in Connecticut; by 1774, that had grown to 5,100.

“The effects of the New England slave trade were momentous,” wrote Lorenzo Johnston Greene in The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776. “It was one of the foundations of New England’s economic structure; it created a wealthy class of slave-trading merchants…”

Harvard Professor Bernard Bailyn, in an essay on how New Englanders had achieved such a high standard of living by the time of the revolution, wrote, “The most important underlying fact in this whole story, the key dynamic force, unlikely as it may seem, was slavery.”

That was only about 3.4 percent of the state’s population, “But it was slavery, nevertheless, that made the commercial economy of 18th-century New England possible and drove it forward,” Bailyn wrote. “The dynamic element in the region’s economy was the profits from the Atlantic trade, and they rested almost entirely, directly or indirectly, on the flow of New England’s products to the slave plantations and the sugar and tobacco industries they serviced.”

As the Black slave population increased, Connecticut’s lawmakers enacted more and more laws to control it, according to David L. Parsons of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute.

The so-called Black Code, a series of laws passed between 1690 and 1730, described the rights and responsibilities of slave and master.

The Black Code formalized slavery in Connecticut. There were no laws specifically forbidding slavery, and custom and the laws controlling it combined to give slavery legal standing in Connecticut, according to Parsons. The early Capital Law of 1642, which prohibited stealing “man or mankind” was interpreted to mean only white mankind.

Parsons wrote of how black servants were required to carry passes outside of town or be treated as runaways. Sellers of liquor were not allowed to serve Blacks without permission from their master. It is not clear what was done to Blacks who drank without permission. Blacks were not allowed to sell items without proof of ownership or written permission from the owner. Blacks were liable to whippings for disturbing the peace or “offering to strike a white person.” Blacks found outside after 9:00 p.m. without a pass could be whipped. Whipping was also the punishment for slaves who used unseemly language.

In 1769, a man named Bishop built the Oakdale Tavern in Wallingford to serve travelers between Boston and New York. “On the hillside in the rear of of the tavern were several cabins where slaves employed on the place dwelt,” wrote a local historian, Bill Stevens. (Source: “Bill Stevens Relates,” Meriden Record, April 8, 1954)

As late as 1774, the Connecticut Journal justified the subordinate status of blacks, stating baldly that “God formed [blacks] … in common with horses, oxygen, dogs etc. for the white people alone, to be used by them either for pleasure or to labor with other beasts.”

That same year the April edition of The Connecticut Journal reported that a slave, Lemon, was “taken to the gaol in New Haven for abusing an Indian girl.” (Source: Clipping, “Tales of Other Days,” by Lavinia, Meriden Record, undated)

On the eve of the American Revolution, Connecticut had 6,464 slaves, the most of any state in New England, according to one historian. The number of whites in the state that same year was 191,372, the state’s governor reported.

Some of those slaves tried to run away, generating advertisements in local papers seeking their return. Two 1761 ads specifically referred to runaway slaves from Wallingford:

Date December 5, 1761

Author(s) David Cook

Runaway(s) Jack

Location Wallingford, CT

Language Skills speaks english well

Reward 5 dollars

Transcription

RUN away from the subscriber in Wallingford, on the 28th of November. A negro man-servant named Jack at middling stature is marked with the Small-pox, speaks good english, had on when he ran away, a red duffel coat, a blue jacket without sleeves, leather breeches, and an old frock. He has some scars from the whip on his back, whoever should take up said negro, and return him back to his said master or secure him in any of his majesty’s gaols, shall have five dollars reward, and all necessary charges paid by me David Cook jun. Whoever shall apprehend said Runaway, are desired to secure him in Irons.

Newspaper New-London Summary

Date June 26, 1761

Author(s) David Cooke, Charles Whittlesey

Runaway(s) Tony, Tully

Location Wallingford, CT

Language Skills Both good english

Reward 40 shillings

Transcription

RANAWAY on the 10th of June, (at Night) from David Cooke of Wallingford, a Molatto Man servant, named TONY, about 26 Years old, middling statute, speaks good English, one sore leg, and is bigger than the other. He had on when he went away a light coloured broad cloth coat, light camblet jacket tow shirt and trowsers. Also, RUN-AWAY the same Night from Charles Whittlesey, Eso; of Wallingford aforesaid. A Molatto Man servant, named TULLY, about 28 years old, speaks good English, about 6 feet high, he has long hair. He had on a dark broad cloth coat, tow shirt and trowsers. Whoever shall take one or both of the above servants, are desired to secure them in irons, and give Notice to their said masters, for which they shall have Forty Shillings reward for each and all necessary charges paid by David Cooke, Charles Whittlesey.

During the American Revolution (1765 – 1783), when at least 820 free and enslaved African Americans from Connecticut served on the Patriots side, some Connecticut slaves gained their freedom in exchange for service (The National Mall Liberty Fund has collected a list of Enslaved and free blacks from Wallingford, CT who served on the patriot side during the Revolutionary War.).

Other slaves purchased their freedom. Wallingford’s archives include an April 2, 1776 note about a local man, Mr. Elisha Brackett, freeing his “Negro Wench Slave named Nancy” in return for her paying him “32 Pounds Lawful money.”

Connecticut’s Gradual Emancipation Act of 1784 halted the importation of slaves and declared that children of black slaves born after March 1, 1784 were to be freed after turning 25. No current slaves were freed by the Act, however, and slaves born before 1784 remained slaves for life.

Not only that, but the act had a pernicious effect in that it encouraged some slaveholders to sell slaves and their children to residents of other states before the children reached 25, an action not prohibited by the law, where they would again be slaves for life.

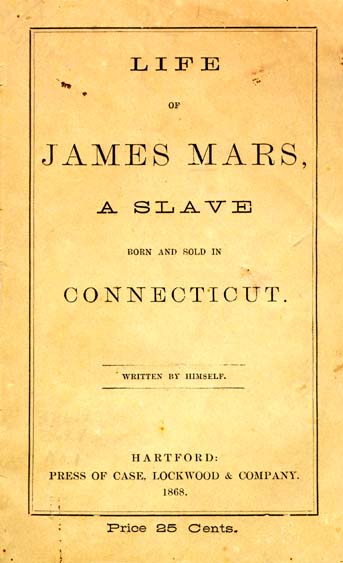

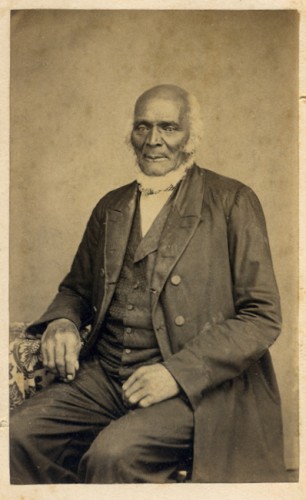

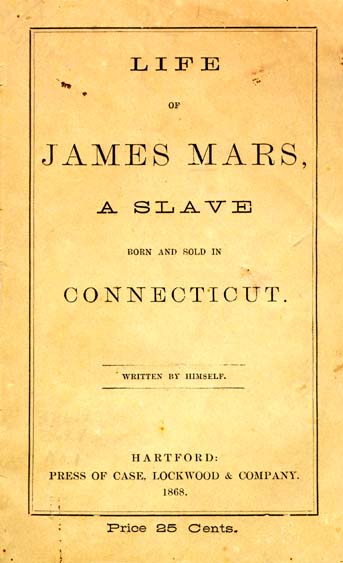

One man affected by the Gradual Emancipation Act was James Mars, a slave in Connecticut until age 25, who wrote a memoir published in several editions between 1864-1876. “When I had got it written, as it made more writing than I was willing to undertake to give each of them one, I thought I would have it printed, and perhaps I might sell enough to pay the expenses, as many of the people now on the stage of life do not know that slavery ever lived in Connecticut,” Mars wrote

Documenting the American South, a collection of American slave narratives, tells of how, with the help of white citizens of Norfolk, CT, Mars evaded his owner’s attempts to take him to Virginia where he would have been denied the emancipation guaranteed him at age twenty-five under Connecticut law. Born in 1790, Mars lived until 1880.

Some historical writing on American history downplays the maintenance of slavery in Connecticut after the American Revolution and the Gradual Abolition Act.

In Hope of Liberty, James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton wrote, “ [m]any slaves were freed by the gradual emancipation laws in the North, and in a relatively short time (relative to the existence of the institution of slavery) slavery was abolished in the free states.”). Similarly, in Black Odyssey: The African-American Ordeal in Slavery“…after the Revolutionary War] [t]hose states of New England, where there was a slight investment in slave property, were rather quick to disavow the institution.”

But other historians have challenged that view. In a 2001 Yale Law Journal article, Abolition Without Deliverance: The Law of Connecticut Slavery 1784-1848 , David Menschel presented evidence that the Gradual Abolition Act did not remove slavery from the state in a prompt and orderly fashion at all. Instead, he said, slavery’s termination was protracted because, “Legislators feared that uncivilized and uneducated blacks, emerging en masse from bondage into freedom, would endanger the fragile workings of Connecticut’s new republic.”

“In fact, though the number of slaves in the North declined after the Revolutionary War, slavery continued to exist there well into the nineteenth century,” Menschel said.

Even the State of Connecticut itself seemed to endorse continued slavery when, in 1784, it seized the estate of a William Brown, which included a number of slave children. An administrator of the estate petitioned the Legislature to free the children, but it rejected the petition and ordered that the children be bound out for the District of Norwich.

“In addition to protecting the state coffers from the costs of caring for such dependents, the Assembly also seems to have believed that Brown’s former slaves would benefit from bondage, as this would ensure that the slave children would be ‘well governed and educated,’ ” Menschel said.

In 1787, Oliver Ellsworth, a Connecticut delegate at the Constitutional Convention, predicted that “slavery in time will not be a speck in our country,” but “in time” proved to be long-lived, with slavery not ending across the United States for another 78 years.

It wasn’t until 1788 that legislation outlawed the slave trade in Connecticut, prohibiting the import of Africans and the export of Africans for sale, but in 1794 the state legislature firmly rejected a bill that would have abolished slavery in the state the following year.

In 1790, the first Federal Census showed there were 3,763 people held in bondage throughout New England, including 2,648 in Connecticut. A 1797 act changed the emancipation age under the Gradual Abolition Act age to 21, but still didn’t abolish slavery.

Evidence of continued slavery in Connecticut showed up in Probate Court records of Wallingford, CT following the death of a Dr. William Hart. According to the records, among the items Hart left to his wife, Catherine Vallet Hart, were “a Negro boy named Titan and a Negro girl of five years.” (Source: Clipping, “Tales of Other Days,” by Lavinia, Meriden Record, undated)

By 1800, 83 percent of Connecticut’s Blacks were free, leaving 951 enslaved, but these were still being held onto vigorously, as the 1803 runaway slave ad below shows.

In the early 1800s, George Washington Stanley completed a census of Wallingford, CT at the request of Yale professor Benjamin Silliman. Stanley’s report said the village had 2,325 inhabitants, including “1,152 white males, 1,147 white females , 22 (people) of color and four slaves…” (Source: Clipping, “Tales of Other Days,” by Lavinia, Meriden Record, Feb. 1953)

In 1810, the number of slaves in Connecticut had gone down to 310 and by 1820 the census put the number at 97.

The 1840 Census showed 17 African-Americans still enslaved in Connecticut, but anti-slavery attitudes were prominent.

Even free blacks began to speak up. The words of one free black man, Peter Osborne, are preserved in “An oration delivered before the people of color of New Haven, assembled at Wallingford on the eighth of July, to celebrate the fourth.”

In vivid, forceful language, Osborne applauded the displays of patriotism on the 4th of July 1845, but castigated white Americans for not sharing the freedom the American Revolution produced.

“The heroes of the revolution were gallant and terrible to establish and secure a government for the peace and happiness of the descendants of Europe, but they were not the less so to deprive the descendants of Africa of its protection,” Osborne said. He called upon all blacks to “…like a Roman army, invade prejudice, storm the castle of expediency, — to annihilate the inhuman trade of transportation–the deluded scheme of Colonization, the scourge and curse of slavery.”

Connecticut finally abolished slavery entirely in 1848, when there were just six slaves left in the state, making it the last state in New England to fully abolish slavery. The last slave in Wallingford was owned by J. Parker of Pond Hill, according to A History of Wallingford 1669-1935 and Wallingford 1669-1935, produced for Connecticut’s Tercentenary Celebration.

It’s not generally known that prior to that point, hundreds of slaves had been owned even by members of Congress from Connecticut.

From the founding of the United States until long after the Civil War, hundreds of the elected leaders writing the nation’s laws were current or former slaveowners.

More than 1,700 people who served in the U.S. Congress in the 18th, 19th and even 20th centuries , including 13 from Connecticut, owned human beings at some point in their lives, according to a Washington Post investigation of censuses and other historical records that revealed its findings in January 2022.

People looking today for records of slaves with a connection to Connecticut can turn to Enslaved.org The database, which gathers records about the lives of enslaved Africans and their descendants has been undergoing a crowdsource-powered expansion to unlock Black Americans’ genealogical histories. The general public and outside researchers can submit family histories, runaway slave ads, or documents of purchase to the site and users can search their names and town histories and connect the experiences of enslaved people, from voyages to the changing of names.

Jessica Ann Mitchell Aiwuyor, founder of the National Black Cultural Information Trust, said African Americans have long sought to reclaim their past. “Even after the Civil War, former enslaved people put ads in newspapers looking for lost family members,” she said. “This website is a continuation of that tradition as we look for our past and family but this time in a digital space.”

Even after Connecticut abolished slavery, the New England states were far from welcoming to Black people. According to the Wall Street Journal, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 revived the long-held fears of many white Northerners that “hordes” of newly freed slaves would flood their cities in search of jobs and housing. Sooner or later, warned the New York Daily News, “we shall find negroes among us thicker than blackberries.”

And as late as 1976, slavery in Wallingford was still being depicted as a benevolent practice. From These Roots, A Bicentennial History of a New England Town, published in 1976, said slavery in Wallingford “was a benign form of ownership here mostly confirmed to household service.” The history went on to say slavery in the town “never attained any importance and the slim records seem indeed often to picture a strong and affectionate relationship.”

We should know these things.

As Holocaust survivor and scholar Dr. Dori Laub has written, we must face our buried truths in order to live our lives.

Addendum – June 19, 2020: With increased interest in Juneteenth, some additional information may be of interest. Juneteenth is a day that commemorates the end of slavery in the United States, but on that day — June 19, 1865 — when Texas slaves were finally notified they were free, thousands of other Black Americans remained in bondage.

According to the Boston Globe, There were four Union border states — Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri — that did not secede. The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in Confederate states, but not in those four Union states.

Granted, most whites in those states did not own slaves, and slaves made up relatively small percentages of the population, from 1.6 percent in Delaware to 19.5 percent in Kentucky, according to encyclopedia.com. In contrast, slaves were 29 percent of the total population of the Upper South and 47.5 percent of the Deep South.

But percentages don’t matter: By 1860, there were 225,483 slaves in Kentucky, 114,931 in Missouri, 87,189 in Maryland, and 1,798 in Delaware.

Maryland abolished slavery in 1864, and Missouri followed in 1865. But many Black Americans in Kentucky and Delaware remained enslaved until the 13th Amendment was ratified in December of 1865 — six months after Juneteenth.

______________________________________________________________________________

- With so many years gone by since the 13th amendment was ratified in 1865, you might think that it has to be impossible to hear a former slave talk about the experience. But amazingly you still can by going to Voices from the Days of Slavery: Former Slaves tell their Stories – a collection on file at the Library of Congress and available online . Here individuals give firsthand accounts of life during slavery. Hearing the voices of those who were enslaved is more powerful than what could ever be captured in a textbook.

2. Recommended readings about Oregon’s racist past:

Breaking Chains – Slavery on Trial in the Oregon Territory by R. Gregory Nokes

Tells the story of the only slavery case ever adjudicated in Oregon courts—Holmes v. Ford. Drawing on the court record of this landmark case, Nokes offers an intimate account of the relationship between a slave and his master from the slave’s point of view. He also explores the experiences of other slaves in early Oregon, examining attitudes toward race and revealing contradictions in the state’s history.

When Portland banned blacks: Oregon’s shameful history as an ‘all-white’ state, Washington Post, June 7, 2017

Few people are aware of Oregon’s history of blatant racism, including its refusal to ratify the 14th and 15th Amendments of the Constitution.

Oregon Racial Laws and Events, 1844-1959

Oregon’s Provisional Government passed the first Exclusion Law in the Oregon Country in 1848. It made it unlawful for any Negro or Mulatto (of mixed ethnic heritage) to reside in Oregon Territory.

Oregon’s Civil War – The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest by Stacey L. Smith

The persistent myth that Oregon was a free land where white unity against slavery made free-state status nearly inevitable often obscures the prominence of the slavery question in provisional, territorial, and state politics.