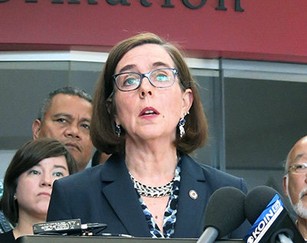

Governor Kate Brown signs the bill to raise Oregon’s minimum wage, March 2, 2016

If you listen just to Democrats in the Oregon Legislature, the just-signed law upping the minimum wage is an unalloyed victory for all.

Tell that to Oregon universities that are faced with big pay increases and to the students who aren’t going to get a job because their school can’t afford to pay them.

According to The Oregonian, Oregon’s new minimum is likely to lead to cutbacks in student hiring or in the number of hours they’re allowed to work, and possibly higher tuition to cover added costs.

At the University of Oregon, the annual wage increases will translate into an estimated $2.3 million in additional wages

In the 2017-19 biennium, $3.4 million in the next funding cycle and $6.1 million by the 2021-23 biennium.

With similar impacts expected at Oregon State University, the school could be looking at reducing the number of student jobs by 650 to 700 positions by FY2019 to cut costs, said OSU spokesman, Steve Clark.

Small businesses across the state are agonizing over the minimum wage increases, too. They’re not going to be talking about ‘What do we do to expand? What do we do to hire more people?’,” said Anthony K. Smith, Oregon state director for the National Federation of Independent Business.

“They’re going to be making some very difficult decisions, none of which are going to help them grow. They have to decide whether to reduce hours for employees, raise prices on customers, make a reduction in their workforce, relocate their business, or maybe even close their doors.

Then, of course, Oregon’s minimum wage changes will contribute to the increased hodgepodge of pay rates in the Pacific Northwest.

If you are an employer in the Pacific Northwest, the minimum wage you will have to pay your employees early next year could, depending on the type and specific location of your business, the age of the employee, and other factors, be any one of the following: $8.05, $9.25, $9.47, $10.15, $10.50, $12.00, $12.50, $13.00, $15.24, $10.35, $11.15, $14.50, $15.00, or $15.24.

If you have to pay prevailing wage rates, your minimum wage rate will be even more expansive. In Oregon, for example, if an employer chooses to include the fringe rate with the basic hourly rate, the minimum hourly wage will be $57.26 for a boilermaker, $52.36 for a dredger and $34.31 for a Highway & Parking Striper.

Clearly, the plethora of minimum wages is going to generate maximum confusion for employers and employees alike. What a mess.

Want to know the whole bewildering picture? See below.

FEDERAL

2016 Federal hourly minimum wage: $7.25 an hour

Federal (sub) Contractors hourly minimum wage

Rate: $10.15. Calculated annually based upon cost of living and rounded to the nearest multiple of $0.05

WASHINGTON

2016 Washington hourly minimum wage outside Seattle, SeaTac and Tacoma: $9.47

- 14- and 15-year-olds may be paid 85% of the minimum wage ($8.05).

- Businesses may not use tips as credit toward minimum wages owed to a worker.

- Under Initiative 688, approved by Washington voters in 1998, the state makes a cost-of-living adjustment to its minimum wage each year based on the federal Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) (www.ssa.gov). The state’s minimum wage is recalculated each year in September. Th4 new wage takes effect the following year on January 1.

2016 Seattle hourly minimum wage

A wage includes salary, hourly pay, commissions, piece-rate, and non-discretionary bonuses. Wages do not include tips or payments towards medical benefits. However, payment toward medical benefits can reduce employers’ minimum wage requirements temporarily until 2018.

Small Employers – 500 or fewer employees

To calculate employer size, count the employer’s total number of individual employees worldwide. For franchises, count all employees in the franchise network.

All small employers are required to pay minimum compensation. Small employers can meet this requirement in two ways:

- Pay hourly minimum compensation rate; or

- Pay hourly minimum wage and make up the balance with employee tips reported to the IRS and/or payments toward an employee’s medical benefits plan. For an employee’s medical benefits to qualify toward the minimum wage, the plan must be the equivalent of a “silver” level or higher as defined in the federal Affordable Care Act. An employer cannot pay a reduced minimum wage if the employee declines medical benefits or is not eligible for medical benefits.

- Hourly Rate

Small employers pay hourly minimum compensation rate based on the following schedule:

| |

Minimum Compensation |

| 2016 (January 1) |

$12.00/hour |

| 2017 (January 1) |

$13.00/hour |

| 2018 (January 1) |

$14.00/hour |

| 2019 (January 1) |

$15.00/hour |

- Tips and/or Medical Benefits

Small employers pay an hourly minimum wage and reach the minimum compensation rate through employee tips reported to the IRS and/or payments toward an employee’s medical benefits plan. If the tips and/or payments toward medical benefits do not add-up to the minimum compensation rate, the small employer makes up the difference.

| |

Minimum Compensation |

Minimum Wage |

| 2016 (January 1) |

$12.00/hour |

$10.50/hour |

| 2017 (January 1) |

$13.00/hour |

$11.00/hour |

| 2018 (January 1) |

$14.00/hour |

$11.50/hour |

| 2019 (January 1) |

$15.00/hour |

$12.00/hour |

| 2020 (January 1) |

$15.75 |

$13.50/hour |

| 2021 (January 1) |

$16.49 |

$15.00/hour |

In 2025, small employers will pay the same minimum wage rate as large employers and will no longer count employee tips and/or payments toward an employee’s medical benefit plan toward minimum compensation. The City of Seattle will calculate percentage changes to the minimum wage based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Large Employers: 501 or more employees

To calculate employer size, count the employer’s total number of individual employees worldwide. For franchises, count all employees in the franchise network.

Large employers can meet Seattle’s minimum wage requirements in two ways:

- Pay hourly minimum wage; or

- Pay reduced hourly minimum wage if the employer makes payments toward an employee’s silver level medical benefits plan. For an employee’s medical benefits to qualify toward the minimum wage, the plan must be the equivalent of a “silver” level or higher as defined in the federal Affordable Care Act. An employer cannot pay a reduced minimum wage if the employee declines medical benefits or is not eligible for medical benefits.

- Hourly Rate

Large employers who do not pay towards an employee’s medical benefits plan pay hourly minimum wage based on the following schedule:

| |

Minimum Wage |

| 2016 (January 1) |

$13.00/hour |

| 2017 (January 1) |

$15.00/hour |

- Medical Benefits

Large employers who do make payments toward an employee’s medical benefits plan pay a reduced minimum wage based on the following schedule:

| |

Minimum Wage |

| 2016 (January 1) |

$12.50/hour |

| 2017 (January 1) |

$13.50/hour |

| 2018 (January 1) |

$15.00/hour |

Once Seattle’s minimum wage reaches $15.00/hour, payments toward medical benefits no longer impact employees’ minimum wage. In subsequent years, the City of Seattle will calculate percentage changes to the minimum wage based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

SeaTac Minimum Wage

Rate: $15.24 for workers in and near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

Tacoma, WA hourly minimum wage

11/04/15 – Tacoma, WA voters approved a $12 city minimum wage phased in over two years. The new minimum wage will apply to most employees who work 80+ hours per year within Tacoma city limits and begins with an increase to $10.35 an hour on February 1, 2016, Jan.1, 2017: $11.15; Jan. 1, 2018: $12.

OREGON

Current: $9.25

Tier 1 (the Portland urban growth boundary)

July 1, 2016: $9.75

July 1, 2017: $11.25

July 1, 2018: $12

July 1, 2019: $12.50

July 1, 2020: $13.25

July 1, 2021: $14

July 1, 2022: $14.75

Tier 2 (Benton, Clackamas, Clatsop, Columbia, Deschutes, Hood River, Jackson, Josephine, Lane, Lincoln, Linn, Marion, Multnomah, Polk, Tillamook, Wasco, Washington and Yamhill counties)

July 1, 2016: $9.75

July 1, 2017: $10.25

July 1, 2018: $10.75.

July 1, 2019: $11.25

July 1, 2020: $12

July 1, 2021: $12.75

July 1, 2022: $13.50

Tier 3 (Malheur, Lake, Harney, Wheeler, Sherman, Gilliam, Wallowa, Grant, Jefferson, Baker, Union, Crook, Klamath, Douglas, Coos, Curry, Umatilla and Morrow counties)

July 1, 2016: $9.50

July 1, 2017: $10

July 1, 2018: $10.50

July 1, 2019: $11

July 1, 2020: $11.50

July 1, 2021: $12

July 1, 2022: $12.50

Milwaukie hourly Minimum Wage for city employees

10/22/15 – The Milwaukie City Council adopted a $15 minimum wage for all city employees. The resolution passed unanimously, putting in place a $15 minimum wage for not only full-time employees of the city of Milwaukie, but also part-time and seasonal workers, as well as interns.

Prevailing Wage Rates

In January and July of each year, Oregon’s Bureau of Labor and Industries publishes the prevailing wage rates that are required to be paid to workers on non-residential public works projects in the state of Oregon. Quarterly updates are published in April and October.

REGION #2

Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington Counties

Under the Davis-Bacon Act, employers can either choose to pay the fringe benefits as additional cash wages (which would result in an effective hourly wage of $38) or provide a “bona fide” benefit plan. Benefits that might be included in such a plan are retirement accounts (401(k) or pensions), medical insurance, vision insurance, dental insurance and life insurance.

Basic hourly rate Fringe rate

Boilermaker $33.92 $23.34

Dredger $39.08 $13.28

Fence constructor

(non-metal) $24.10 $10.12

(Metal) $20.50 $ 5.09

Highway & Parking

Striper $26.11 $ 8.20